| Journal of Current Surgery, ISSN 1927-1298 print, 1927-1301 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Curr Surg and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.currentsurgery.org |

Case Report

Volume 9, Number 2-3, September 2019, pages 32-37

Proximal Radius Ewing’s Sarcoma Resection Followed by Migration of the Proximal Radius: Report of Two Cases

Wazzan Al-Juhania, Mohammed Benmeakelb, c

aKing Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences (KSAU-HS), King Abdulaziz Medical City (KFH-KAMC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

bKing Fahad Hospital, King Abdulaziz Medical City (KFH-KAMC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

cCorresponding Author: Mohammed Benmeakel, King Fahad Hospital, King Abdulaziz Medical City (KFH-KAMC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Manuscript submitted June 21, 2019, accepted July 3, 2019

Short title: Proximal Radius Ewing’s Sarcoma Resection

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcs383

| Abstract | ▴Top |

We present two young patients who developed Ewing’s sarcoma in the proximal radius, managed surgically by resection and no reconstruction with K-wire fixation of the distal radioulnar joint for 6 weeks. Following surgery, both patients developed proximal radius migration with subluxation, which caused the patients to complain about deformation. Proximal radius migration with subluxation is well documented in trauma cases, although they were not described in orthopedic oncology since reconstruction was the classic management for such cases. Our results support the decision of reconstructing the proximal radius after resection in order for better functional outcome and stability.

Keywords: Ewing’s sarcoma; Proximal radius resection; Migration of the proximal radius

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Ewing’s sarcoma is considered a highly malignant tumor of bone and soft tissue. One of the anatomical classifications of Ewing’s sarcoma is skeletal or extraskeletal. Most cases of Ewing’s sarcoma arise from the bone, and only one-third of the cases are soft tissue sarcomas [1, 2]. The epidemiological data available on such tumor showed incidence rate of 1 - 3 cases per million population [3]. Skeletal Ewing’s sarcoma is found more in association with long bones followed by pelvis, chest wall and lastly in the spine (47%, 26%, 16% and 6%, respectively). Ewing’s sarcoma presenting in the proximal radius is extremely rare [3, 4].

Treatment options for Ewing’s sarcoma are chemotherapy and surgery with possibility of using radiotherapy. Over years of research, oncologist found that surgery is more effective than radiotherapy, in terms of prognosis, function and risk of secondary malignancy that is caused by radiotherapy. Radiotherapy has been used in case of inoperable Ewing’s sarcoma or if the surgical margin was positive. Using radiotherapy as a single treatment is associated with higher risk of recurrence [5, 6]. Moreover, surgical management was found to be the best intervention after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy when compared to radiation therapy alone or a combination of surgery and radiation [7].

Surgical options included resection of the tumor with or without reconstruction, and it can go even to amputation of the whole limb, which has been rarely done after the improvement and advances in diagnosis and controlling such malignant tumor [3]. Surgical complications vary and depend on many factors, including patient or surgical approach factors. These complications can be infection, loss of function, wrist or elbow pain, or even recurrence [8, 9]. We present two cases with rare presentation of forearm mass, which were diagnosed as Ewing’s sarcoma, and one of the complications that can be faced after resection without reconstruction with temporary fixation of the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) with K-wire for 6 weeks. Both patients were consented for all procedures.

| Case Reports | ▴Top |

Case 1

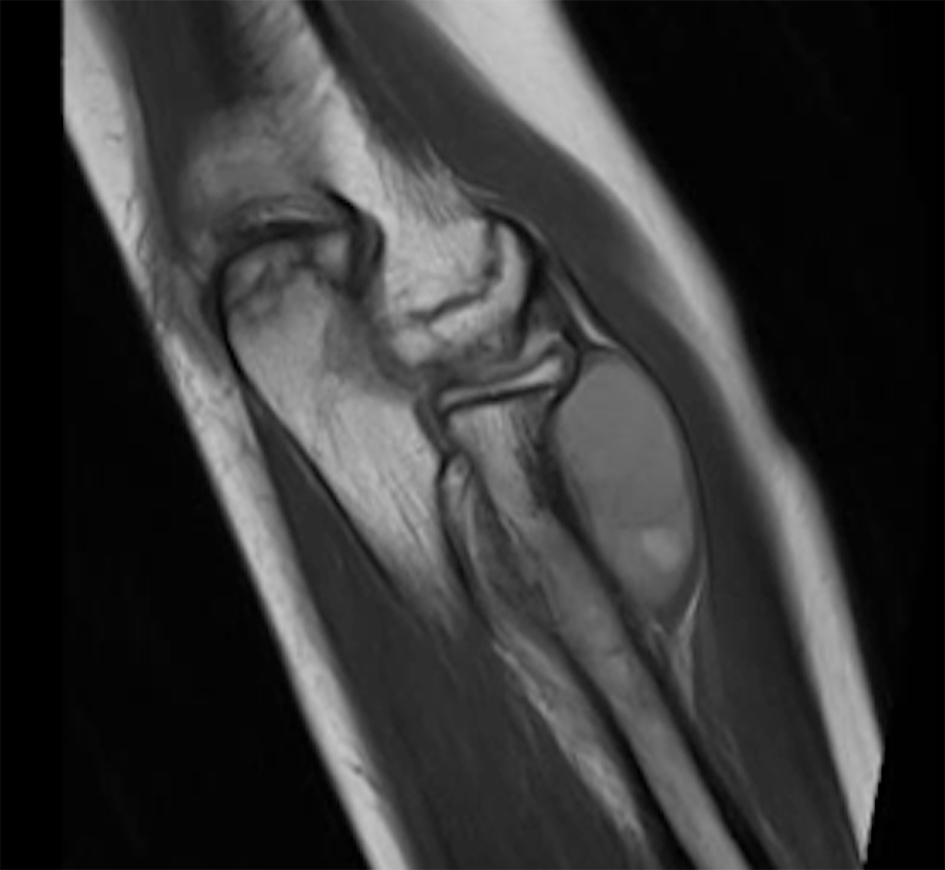

A 14-year-old boy presented to our orthopedic oncology clinic with left forearm swelling. This swelling was associated with pain and lasted for 6 months; it was increasing in size and not associated with any decrease in range of motion of the elbow or wrist. A multidisciplinary team was involved in diagnosing and managing the patient. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the forearm showed a mass around the proximal radius sparing the medial side and measuring 3.2 × 3 × 4.1 cm (Fig. 1). As reported by musculoskeletal radiologist, the mass origin looked a skeletal with extension to the soft tissue. After obtaining biopsy by intervention radiology team, pathology report showed morphology and immunohistochemical features consistent with Ewing’s sarcoma.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Magnetic resonance imaging of the forearm with a mass measuring 3.2 × 3 × 4.1 cm (coronal cut). |

Then, the patient received neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for four cycles. After that the patient was admitted under orthopedic team for elective resection of the proximal forearm mass. After resection, chemotherapy was used without radiotherapy as adjuvant because of the negative margin post resection.

Surgical technique

Under the effect of general anesthesia, the patient was put in a supine position. Going through a dorsal approach, over the left dorsal radius, the posterior interosseous nerve was identified and protected at the course of the resection site. A previous templating by the MRI showed resection of 10 cm of the bone was necessary in a wide margin fashion. After resection, the biceps tendon was attached to the ulnar, and two K-wires were inserted in the distal radio-ulnar joint under fluoroscopy. The purpose of the K-wire was to prevent subluxation of the DRUJ.

Follow-up

The patient was followed 2 weeks after surgery to examine the wound to review the post-operational X-rays (Fig. 2). Then he was followed in a 6-week manner for removal of the K-wire after reviewing the follow-up X-rays (Fig. 3). At the 7-month follow-up, we noticed a migration and subluxation of the distal radius causing instability in the DRUJ with positive ulnar variance. The patient complained of deformation with mild discomfort. However, he was not complaining of wrist pain at that point. Long-term follow-up for 3 years did not show any recurrence or musculoskeletal complaints.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Two weeks post-operational X-ray showing proximal radius resection with two K-wires in place. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Six weeks X-ray showing proximal radius resection with two K-wires removed, and an apparent subluxation and migration of the proximal radius. |

The resected tumor was sent for pathology and the report showed microscopic residual Ewing’s sarcoma with approximately 5% viable tumor. The majority of the tumor is replaced by fibrosis and vascular granulation tissue, consistent with therapy effect. Microscopic tumor is within the bone with focal presence in the ventral anterior, medial and dorsal muscular tissue. This is further confirmed by the CD99 (clone 12E7) immunohistochemical stain, which highlighted the focal involvement by the tumor. The tumor is negative for any evident of lymphovascular invasion, and the outer soft tissue margins of resection are all free of tumor.

Case 2

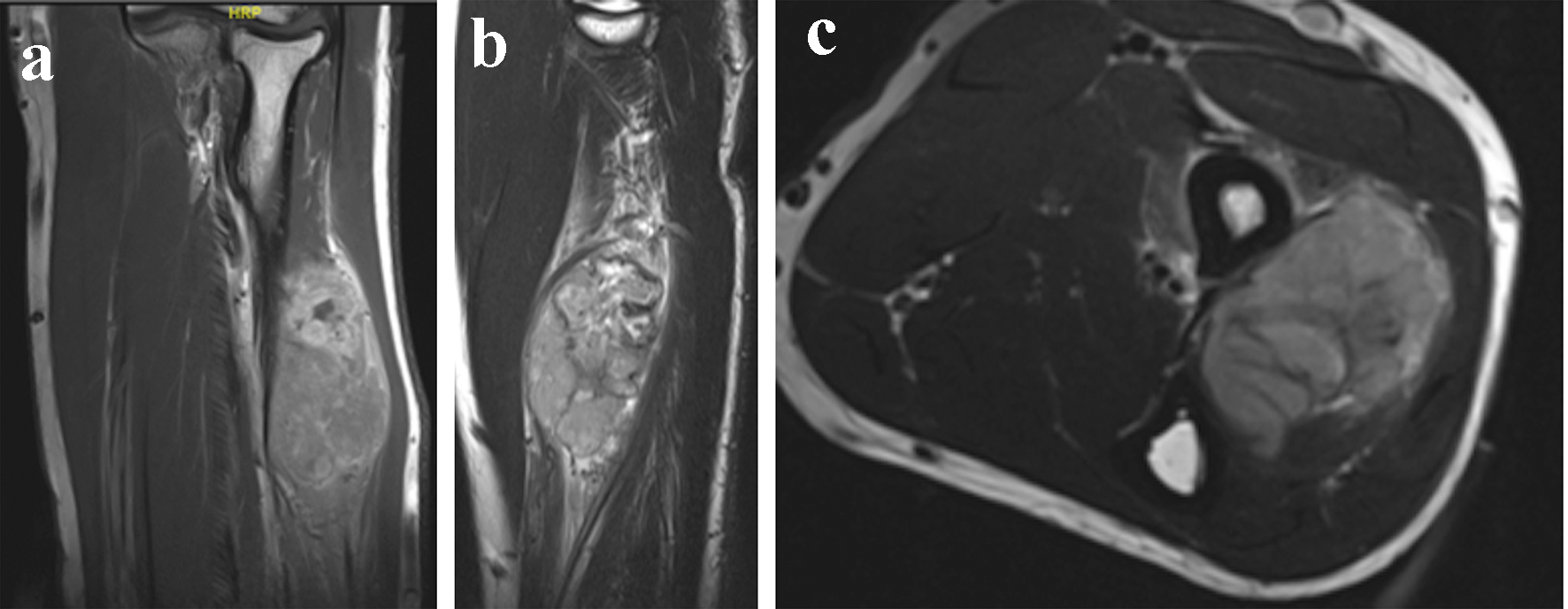

An 18-year-old man presented with a left forearm mass for 9 months. The swelling was increasing gradually and it started as a painless mass, and then became a painful mass. The pain was sudden, severe and sharp in character. MRI of the forearm showed proximal to mid-shaft mass of the radius, measuring 6.4 × 3.5 × 4.2 cm (Fig. 4a, b, and c). Based on the musculoskeletal radiologist, the tumor arised from the bone with soft tissue extension. A core biopsy was done by intervention radiology team and sent for pathology to test for EWSR1 (22q12) by FISH, EWSR1/FL1 and EWSR1/EGR translocation. These were positive and indicated Ewing’s sarcoma.

Click for large image | Figure 4. (a, b, and c) Magnetic resonance imaging of the forearm mass, measuring 6.4 × 3.5 × 4.2 cm in coronal, sagittal and axial cuts, respectively. |

The patient received neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for seven cycles. After 22 days from the last cycle, the patient underwent the surgical management. After surgical management, the tumor board chose chemotherapy and radiotherapy as adjuvant; the reason for that is the pathology report post resection, which showed highly viable tumor post neo-adjuvant chemotherapy.

Surgical technique

This patient underwent dual anesthesia, upper limb block and general anesthesia. The patient was put in a supine position. Then, our approach was dorsally with excision of the biopsy tract according to the musculoskeletal oncology principle. The posterior interosseous nerve was identified and protected, and then soft tissue dissection was done till we reached the proximal radius. An MRI templating was done pre-operation and was followed as 13 cm resection from the elbow joint, which was considered as a wide resection margin. After that, we attached the biceps tendon to the ulnar. Lastly, the distal radio-ulnar joint was stabilized by two K-wires and the forearm was tested in 30 - 35° of supination and pronation.

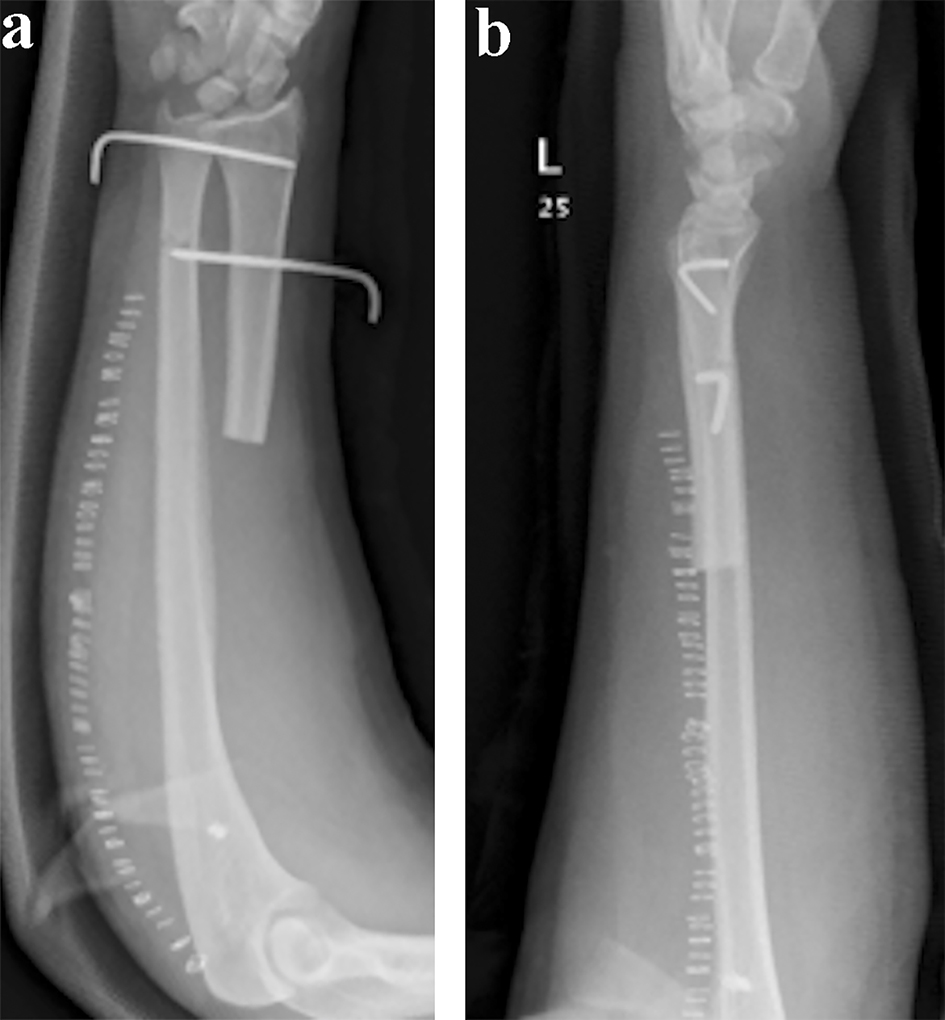

Follow-up

The patient was followed in 2-week, 4-week, 6-week and 12-week fashion. On the 2-week follow-up, the wound was examined, and did not show any sign of infection, and X-rays (Fig. 5a, b) were reviewed to look for proper placement of the K-wires. This follow-up did not show any subluxation or migration of the radius. On 4-week follow-up, one K-wire was removed only. After 2 weeks, the other K-wire was removed (Fig. 6a, b). On both follow-ups, no subluxation was noticed on X-ray or physical exam. The following visit, which was on a 12-week basis, showed a migration with subluxation of radius and presentation of positive ulnar variance. For 2 years follow-up, the patient still did not complain of wrist pain but only a deformation and discomfort. He underwent adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation, and no recurrence was noted.

Click for large image | Figure 5. (a and b) Two weeks follow-up anteroposterior and lateral X-rays showing proximal radius resection with two K-wires in place. |

Click for large image | Figure 6. (a and b) Six weeks post-operational anteroposterior and lateral X-rays showing proximal radius resection with two K-wires removed, and a migration with subluxation of the proximal radius. |

The resected mass was sent for pathology and showed a high grade Ewing’s sarcoma with tumor size of 4 cm in maximum dimension. The tumor firmly adhered to the underlying periosteum with focal microscopic invasion of the cortical bone. The distal osteotomy bone margin was negative. However, the status post neo-adjuvant chemotherapy showed that the tumor is > 99% viable and < 1% necrotic. The specimen was positive for EWSR1 (22q12) gene rearrangement by FISH study and positive for EWSR/FLI-1 fusion transcript.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Ewing’s sarcoma rarely presents in the radius [10]; management of such tumor is surgery and chemotherapy mainly. Many surgical choices were presented over the years; these options include en bloc excision (mainly for benign lesion), resection with/without construction or amputation [11]. It also includes resecting the tumor in a wide margin or in a radical fashion [3]. Each surgical management has its own complication; however, literature did not offer much on resection of the mass without reconstruction in regard to the subluxation of the distal radius after resection. Our two cases presented with this complication that can affect the patients in terms of wrist pain or potential for arthritis. Our patients only complained of deformed appearance and mild discomfort.

In our second patient, we achieved a good range of motion with an acceptable functional status. He was able to supinate and pronate for almost 30°. Giessler et al [12] reported a good function outcome with reconstructing the forearm-resected mass with re-vascularized fibula graft. The flap measures were between 10 and 17 cm in length; however, he reported five cases of forearm masses and one of them was Ewing’s sarcoma only.

Gokaraju et al [13] presented a case series of five patients who had tumors of the proximal radius, one of which was Ewing’s sarcoma. The resected mass was 11 cm in length, and reconstructed with a metal proximal radial endoprostheses. He reported that none of his patients experienced wrist pain, which can be interpreted as no proximal radius migration has happened, although both of our patients had a radius migration but did not develop any wrist pain. The follow-up period for the Ewing’s sarcoma patient was the shortest (10 months); all of his patients had a good functional score on the Mayo elbow performance score.

Dahuja et al [14] had a case of giant cell tumor in the proximal radius; the surgical management that was used in that patient was wide margin excision with reconstruction by a non-vascularized fibula graft and sparing the radial head. His case had an acceptable outcome in terms of wrist pain, stability and range of motion of the elbow in a follow-up of 2 years.

In regard to our presented complication, proximal radial resection including radial head resection without reconstruction was associated with subluxation and proximal migration of the radius despite fixing the distal radioulnar joint with K-wires. Karl et al [15] reported one case of a patient who sustained a radial neck nonunion and treated with radial head excision with staged radial head replacement. His subject was followed for 7 months, the patient started to have wrist pain after 4 months from the operation date and a positive radiograph for subluxation with migration; however, the patient had a good functional status and range of motion. The supination and pronation of her forearm reached 90° [15]. In comparison to our patients, the resection was wider; therefore, the range of motion would be decreased. Although he did replace the defect, the migration was still an issue that caused the patient a wrist pain. Antuna et al [16] in 2010 reported that a larger number of patients (26 cases) underwent primary radial head resections, who were followed for almost 15 years, and only three patients complained of wrist pain with evidence of migration. These results support the need to reconstruct any defect in the forearm for better function and range of motion.

To our knowledge, literature was limited in reporting migration of the proximal radius, subluxation or even wrist pain in Ewing’s sarcoma of the proximal radius after resection without reconstruction. However, in one meta-analysis, Liu et al [17] reported a high rate of complications in en block resection of giant cell tumors of the radius. These complications include arthritis (13-50%) and subluxation (12-67%). However, Vander Griend et al [18] reported that carpal bones were more susceptible to subluxation. He reported also one patient who complained of wrist pain and instability after 2 years of follow-up.

Our two cases were treated with large segment resection and no reconstruction was done for both of them. As our patients were young, prosthesis was not our first choice. In addition, this type of prosthesis needs to be custom made with very high cost and variable complication with limited follow-up in the literature. Both patients did not afford the expenses of such prosthesis. A vascularized fibula could be an option in our cases but the stability option at the elbow was a big concern as our patients refused taking the fibula as an option for reconstruction. Although none of our patients complained of significant wrist pain, the proximal radius migration is a musculoskeletal complication and related to the decision of our surgical management; unfortunately, it can affect the patients’ functional status later during adulthood.

These two cases showed an acceptable functional status with an acceptable forearm range of motion. We think that they are representative but if the patient condition or situation did not allow the surgeon to reconstruct, an acceptable functional result seems to happen. We recommend the choice of reconstructing the defect after excision of proximal radius tumor using prosthesis, allograft or autograft to avoid the risk of wrist pain and the high possibility of deformation which can affect the patient function in the future.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Informed Consent

Both patients were consented regarding every procedure included in the manuscript and to report the cases.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed in management of the patients, editing and writing the manuscript.

| References | ▴Top |

- Applebaum MA, Goldsby R, Neuhaus J, DuBois SG. Clinical features and outcomes in patients with Ewing sarcoma and regional lymph node involvement. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(4):617-620.

doi - Cash T, McIlvaine E, Krailo MD, Lessnick SL, Lawlor ER, Laack N, Sorger J, et al. Comparison of clinical features and outcomes in patients with extraskeletal versus skeletal localized Ewing sarcoma: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(10):1771-1779.

doi pubmed - Daecke W, Ahrens S, Juergens H, Martini AK, Ewerbeck V, Kotz R, Winkelmann W, et al. Ewing's sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor of hand and forearm. Experience of the Cooperative Ewing's Sarcoma Study Group. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131(4):219-225.

doi pubmed - Bolling T, Hardes J, Dirksen U. Management of bone tumours in paediatric oncology. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2013;25(1):19-26.

doi - Heikamp E. 50 Years Ago in The Journal Of Pediatrics: Treatment of Ewing sarcoma with concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy. J Pediatr. 2018;199:193.

doi pubmed - Gaspar N, Hawkins DS, Dirksen U, Lewis IJ, Ferrari S, Le Deley MC, Kovar H, et al. Ewing Sarcoma: Current Management and Future Approaches Through Collaboration. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(27):3036-3046.

doi - Werier J, Yao X, Caudrelier JM, Di Primio G, Ghert M, Gupta AA, Kandel R, et al. A systematic review of optimal treatment strategies for localized Ewing's sarcoma of bone after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. Surg Oncol. 2016;25(1):16-23.

doi - Hamilton SN, Carlson R, Hasan H, Rassekh SR, Goddard K. Long-term outcomes and complications in pediatric Ewing sarcoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2017;40(4):423-428.

doi pubmed - Fuchs B, Valenzuela RG, Inwards C, Sim FH, Rock MG. Complications in long-term survivors of Ewing sarcoma. Cancer. 2003;98(12):2687-2692.

doi - Bellan DG, Filho RJ, Garcia JG, de Toledo Petrilli M, Maia Viola DC, Schoedl MF, Petrilli AS. Ewing's sarcoma: epidemiology and prognosis for patients treated at the Pediatric Oncology Institute, Iop-Graacc-Unifesp. Rev Bras Ortop. 2012;47(4):446-450.

doi - Saridis AG, Megas PD, Georgiou CS, Diamantakis GM, Tyllianakis ME. Dual-fibular reconstruction of a massive tibial defect after Ewing's sarcoma resection in a pediatric patient with a vascular variation. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31(3):297-302.

doi - Giessler GA, Bickert B, Sauerbier M, Germann G. [Free microvascular fibula graft for skeletal reconstruction after tumor resections in the forearm - experience with five cases]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2004;36(5):301-307.

doi - Gokaraju K, Miles J, Parratt MT, Blunn GW, Pollock RC, Skinner JA, Cannon SR, et al. Use of metal proximal radial endoprostheses for treatment of non-traumatic disorders: a case series. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(12):1685-1689.

doi pubmed - Dahuja A, Kaur R, Bhatty S, Garg S, Bansal K, Singh M. Giant-cell tumour of proximal radius in a 50-year-old female with wrist drop: a rare case report. Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2017;12(3):193-196.

doi - Karl JW, Redler LH, Tang P. Delayed Proximal Migration of the Radius Following Radial Head Resection for Management of a Symptomatic Radial Neck Nonunion Managed with Radial Head Replacement: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Iowa Orthop J. 2016;36:64-69.

- Antuna SA, Sanchez-Marquez JM, Barco R. Long-term results of radial head resection following isolated radial head fractures in patients younger than forty years old. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(3):558-566.

doi pubmed - Liu YP, Li KH, Sun BH. Which treatment is the best for giant cell tumors of the distal radius? A meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(10):2886-2894.

doi pubmed - Vander Griend RA, Funderburk CH. The treatment of giant-cell tumors of the distal part of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(6):899-908.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Current Surgery is published by Elmer Press Inc.